Hand to mouth

Early GVG logo in string art

At first GVG had a hard time enticing engineering talent up into the Sierra foothills, still considered by many as a technological backwater where not much challenging could be going on. In a stroke of luck, Hare finally landed a bay area engineer from Varian and Associates, Bill Rorden. He somewhat reluctantly made the move. He was another Stanford graduate who was well respected at Varian and had been promoted into management, which he realized that he did not like and was ready for a change. Right away Rorden and Roy Hamme, and early DCG Hare company employeem went to work redeveloping the vacuum tube amplifiers for Cinerama using solid state components. While Rorden was a vacuum tube engineer, he quickly reinvented himself into a solid-state engineer.

Rorden, also liked to fly, and owned a plane. Once when Fling of Cinerama had come to GV for a meeting about the new amplifiers he ended up staying to long and was in danger of missing his plane out of Sacramento. Rorden flew him to Sacramento in time to catch his plane.

By 1960 Hare, who from earlier experience with the Bell Lab employees who had developed solid state devices, and Hamme were probably two of the most knowledgeable people in the country in using the new technology, with Rorden right behind them. The Group, as GVG also was soon called, never designed a product using vacuum tubes. Like another juggernaut in not only the consumer electronics industry, but in the high-end television equipment market, Sony, Grass Valley became a pioneer in using solid-state transistors. Many who grew up in the 60s often took their relatively small Sony transistor radios to bed to listen to music or a ball game while their parents assumed they were asleep. Something that would not have been possible a few years prior.

It did not take long before it became apparent that Litton's and Hare's companies could not coexist in the same building. The strain between the two rapidly got worse. Litton was very fugal and accused GVG employees of using too much toilet paper, paper towels, and office supplies. Litton even had one of his employees separate 2-ply sheets of paper towels so they would go father. Litton's sons, Larry and Charlie, Jr thought they might have played a small role in the growing chasm as they would come home from school and sometimes roam halls over zealously, causing Hare to occasionally yell at them.

It did not help matters that the Group often took over spaces and pieces of equipment that was not part of the lease. The tripping point came when Litton laid off an employee that Hare in turn hired. The two friends never spoke to each other again.

Hare decided they had to move out immediately. All they could find was a rundown structure that had been a processing plant for freezing chickens. One of the groups manufacturing machines was too big to fit through the door so a hole was cut into a wall.

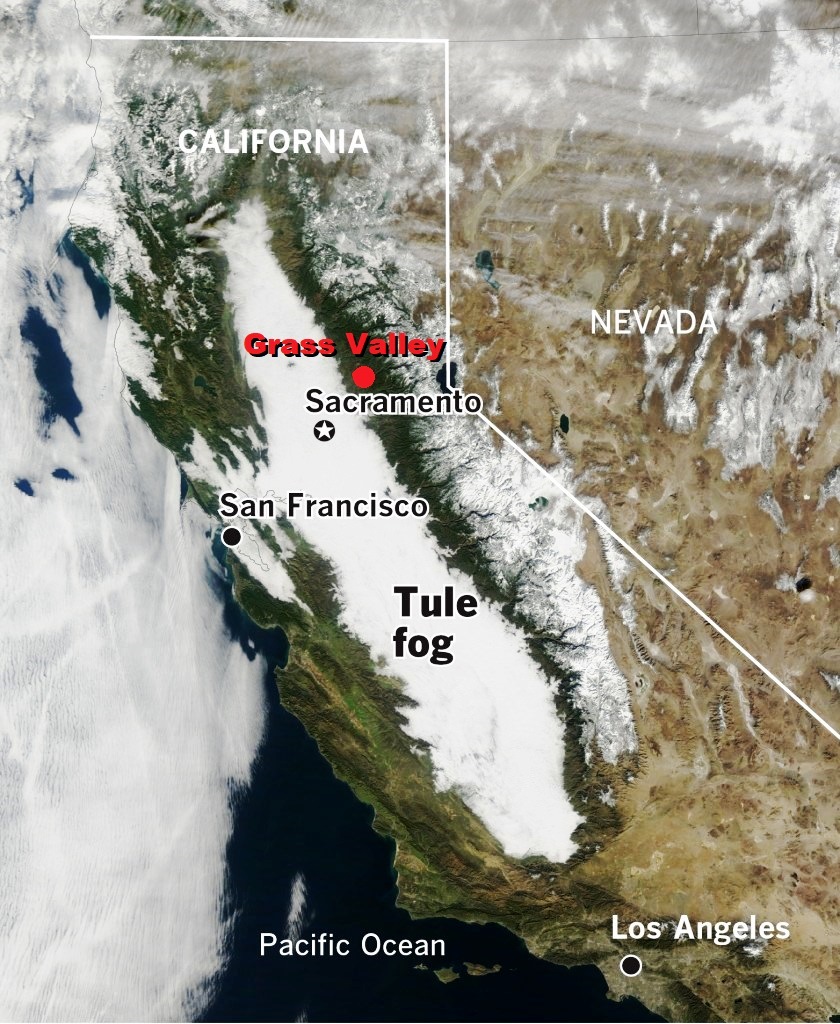

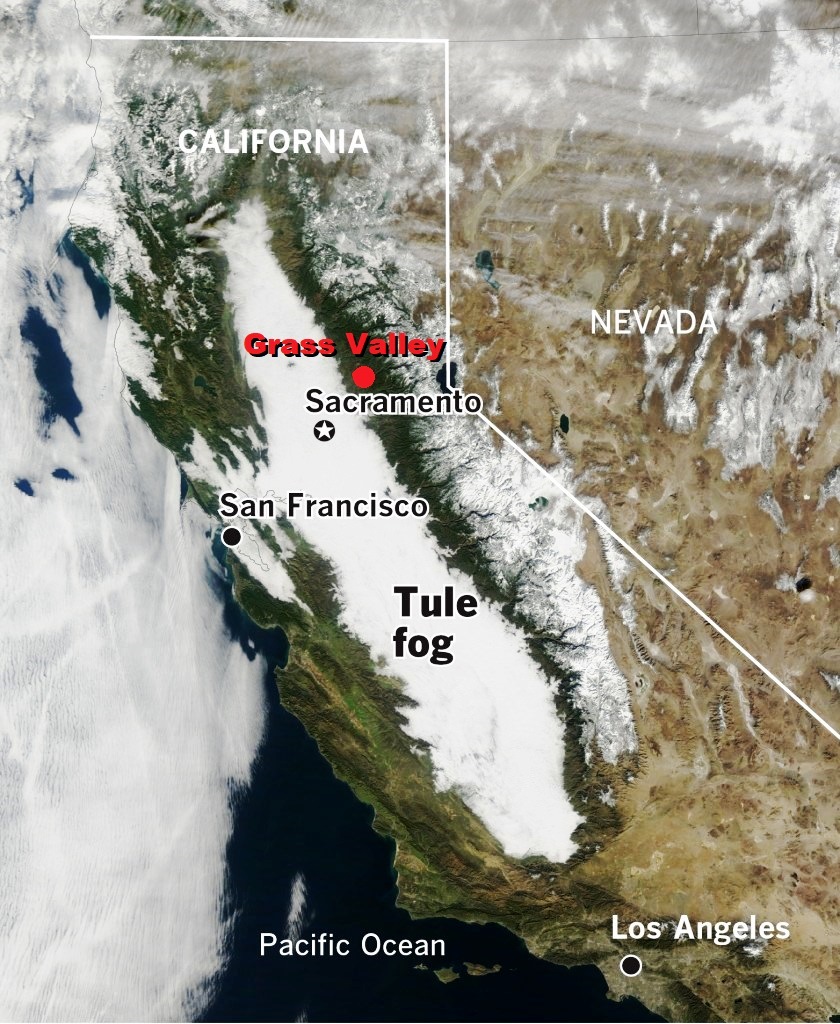

When the Cinerama order was completed in their ramshackle building GVG had an after-tax profit of $120,000. Earlier Hare had started looking for property for the company to eventually settle on. One New Year's Day he took a plane ride and spotted the company's future site. It was northwest of Grass Valley on the south side of a small valley, and it ran up a ridge that overlooked a canyon created by Deer Creek. From the top of the ridge off in the distance you could see the Sacramento Valley and it was at an altitude that allowed it to be above the tule fog layer that often settled into the valley in the winter after heavy rains and chili weather had set in. The site occasionally even saw a dusting of snow.

After periods of rain, and colder temperatures that settle into the central valley, a dense layer of fog often sets in, often for weeks at a time. Or until the next rain storm rolls through

A previous owner apparently had planned some development on the land, as it had been graded. Hare now wanted to buy that 80-acre property. The problem was that the owner wanted $500 an acre, which Hare thought was too much, especially since it did not have any frontage along the road. So, he bought three acres along the road and put out the word that he was starting a chicken ranch, which he might have conjured up by the previous use of their current digs. The price of the 80 acres came down to less than $300. An architect from the bay area designed a functional 4,000 square foot building made of split-blocks with a face resembling stone. The building blended nicely with the sloping ground and Ponderosa Pines. It cost $40,000 to build, with Rorden doing most of the wiring.

The building only had two small luxuries, a small bathroom off Hare's office, which overlooked a small lake, and an exterior wall covered with white, gold-bearing quart rock from the Empire mine. The property also had an "A" frame house built on it for the Hares, on the ridge above the plant, secluded by pines and furs with breathtaking views in three directions, especially in the winter when the skies were more apt to be clear of haze. Often the coast range, one hundred miles distant on the opposite side of the Sacramento Valley was visible.

The site became known as Bitney Springs after the road it was on, which took the name of a local spring.

The actual spring

Hare had an A-Frame house built on a ridge overlooking the GVG campus on the company's property

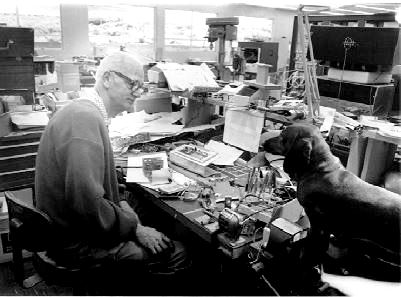

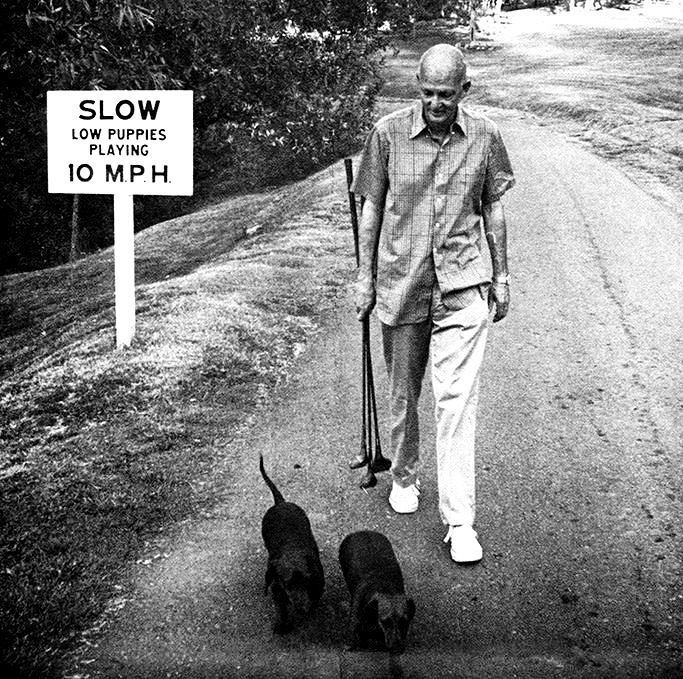

The house had commanding views in three directions. He had two Dash hounds that usually went with him wherever he went, and he drove a five-year-old black Mercedes. Hare used a walking stick which was a battered four iron.

The area at the time had only single-phase power, and the power company wanted $30K to run an additional conductor, to provide the necessary service, down Bitney Springs road that ran past the property from highway 20, about 5 miles away. Hare threatened to file a complaint with the PUC on behalf of himself and the neighboring ranchers. The power company added a fourth conductor and now GVG had three-phase power to run their equipment. For water there was a natural spring on the site which had adequate flow for the present and future needs. Hare had a water tank built up above the building to store the water and provide adequate water pressure.

Forget about finding a market, need to find a business!

Even in their new facility business continued to be slow and weeks passed without any new orders. The Sangamo contract helped keep the company going. Hare and Rorden solved a problem brought to them by the State Department. Many hotels in the Soviet Union had phone systems that allowed the monitoring of what was said in the room even when the phone was not in use. They designed and built a device that could be placed over the phone and generate noise to mask whatever was being said in the room. Associated with that gadget they used a Triplett voltmeter, a standard piece of test equipment at the time, added some components and had a product that the occupant of the room could check to see if their phone line was bugged.

The A.B. Dick company gave GVG a contract to build a forerunner of a fax machine. The end user was a railroad that wanted to scan waybills and manifest data during the day, record it on tape, and then send it at night to destinations when the rates were lower. The tape recorder was a two-speed machine. It would record at high speed, but when sending the data, it would use a slower speed because of interference and bandwidth on the phone lines of the day. While a working system was developed and delivered, it is believed that it was never actually used.

These sundry projects and requests kept trickling in, but the company was continually a few payrolls away from insolvency. To help stem the burn rate Hare often would not cash his paychecks. 1960 was a tough year with Bill Rorden putting his savings of $20K into the company. While the Sangamo contract kept $50K coming in for a couple more years it was glaringly apparent that the Group had to find a market to serve and had to do it quickly.

1962 had been a financial disaster for the group. Now with the Group facing the precipice for a second time Hare knew time was running out. While at the time Dr. Hare, 55, was still in good health and weighed the same as he did in high school, he was worried about having to financially start over. Bill Rorden losing his investment was also weighing on him. The company decided to concentrate on selling audio amplifiers.

Early on the Group did a number of things to survive

From projects for the state department to railroads

they did whatever it took to keep the lights on

They slowly found steady work building audio amps

With some focus on what they were coming to work to produce business picked up slightly in 1963. They made more deliveries of their audio amps, known as models 610, 621, and 622. The company was paying its bills and meeting payroll, but not with much to spare. Even with an increase in orders for their audio equipment, their strategic position did not change much because of the low gross margin caused by intense competition in the audio market. They needed a proprietary product.

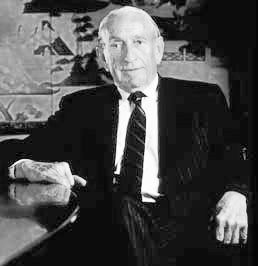

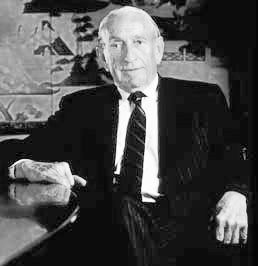

David Packard

A low point in 1963 occurred when a former Stanford physics student of his, David Packard, of Hewlett-Packard, called and said they might have a common interest and should talk. Dr. Hare and Hazel drove down to Palo Alto, and he met with Packard. The meeting went nowhere. On the way back with Hazel behind the wheel Hare had her stop and he bought a pint of J&B scotch. He drank it as they crossed the then two-lane Dumbarton Bridge across the southern end of the San Francisco Bay and by the time they got to the Nut Tree in Vacaville, once a well visited stop along I80 between the bay area and Sacramento, he was sound asleep, and she went inside for a coffee break.

The small company continued casting about for something of subsistence to build the company on. They often talked about the television broadcast market, which was growing, especially with a new group of TV stations powering up on the UHF band. If they knew what they were up against in that market they would have been advised to promptly drop the idea.

Dr. Hare's Management Style

Hare's management approach was very much hands on. From running his company to actual circuit design. He had a workbench by his desk. He usually had one of his dogs by his side.

Hare had a 6 foot plus frame. He had a well-worn but friendly oak swivel chair in his office. Outside his office he had two benches in an L shape, always cluttered with parts, soldering iron, small hand tools, an oscilloscope, and other test equipment. But he kept one clear space. It was for his grown-up Dachshunds, Itsy and Red. That space was for the "puppies" as he would refer to them. He would park both of them in the clear space when he was working at the benches. The "puppies" were the reason for the strict five-miles-an-hour speed limit on the property.

The consulting contract with Sangamo had ended. At this time, an employee of Sangamo, Bob Robertson, who worked in their financial area, was looking for a change in environment because of recurring asthma. Chick, the head of Sangamo, recommended him to Hare, who hired him. Hare liked the idea that during the interview Robertson never asked about benefits. Hare started him low, but after a short while gave him a raise. Bob in 1996 wrote a book about Hare, The Inscrutable Dr. Hare. Bob said in his book that Hare wanted to know what was going on in every department every day. From Robertson he wanted to know each day's cash receipts, disbursements, and bank balance. He checked those totals himself. If he found any errors, he would issue a sharp reprimand.

Hare would at times encourage differences in opinion. He wanted to ensure that the right way to do or approach something was arrived at. So, although he was often right, he would sometimes take a contrarian approach to what he believed was right just to draw out responses from those around him. He often did that with his engineering neighbor, Rorden. Bill would then have to make a logical case for what they were trying to do. Often the original track was confirmed. But sometimes a different and better path forward was realized. According to Bob Robertson, Hare in one meeting responded to a silent room by saying "Dammit, I'm paying you guys too much money to just sit there and agree with me." Hare was the first to admit that he was opinionated and difficult to work for, but many had their lives profoundly influenced by his tenets.

In pushing his troops to question the conventional wisdom they would often find that the discussion had gone full circle. When the same discussion points started to repeat Hare would often say we have been around the mulberry bush already. Rorden once quipped, why not build a revolving mulberry bush.

The group manufactured almost everything in house, including metal cases, printed circuit boards, even shipping cartons. Hare was always worried about customer service and if a piece of equipment was under warranty, even after the company started sending loners, if it was not being repaired right away he demanded an explanation.

Hare was such a creature of habit that he got dressed in a certain order. Underwear, shirt, socks, shoes, and then pants. He would not change even after men's pants tapered narrow at the bottom. Hazel had to find pants that would allow him to continue to dress in that order. First time Bob Robertson met Hare he was casually dressed in a short sleeve Sports shirt and khaki trousers. Quite a contrast to the white shirt, tie, and jacket corporate atmosphere he was used to.

Here he is walking from his house which was also on the site

Hare was competitive in all he did, not only within the company. But company extracurricular activities also. Here he is with his management inner circle during a chip and putt session on company grounds.

At 26 Bob Johnson was hired as a technician and given his first assignment, winding transformers. He had spent 4 years in the air force as a radar tech and worked a year at an electronics company before coming to Grass Valley. His second day at the company Hare stopped and watched him winding transformers. Hare said he was too slow and that he should be able to do it faster. "Do you want quality or speed" was Bob's reply. "I want both!" Hare said. Bob survived and eventually went on to become the most senior employee of the company in terms of service. Bob became part of the after-hours recreation in the plant with Dr. Hare and Stephen Hare. Sometimes it was a putting game with coffee cans placed around the factory. All games had to include small wagers to satisfy the competitiveness of Hare. Sometimes it was targets shot at with pellet rifles at a steel rollup door. Once he brought out a .22. The next day it was realized that there were holes through that door.

Bob was a good golfer and was always included at the Sunday foursome at Alta Sierra Country club. Occasionally Hare would invite Bob to play on a week-day afternoon, just the two of them. Once, when they were having their customary after round drink. Bob mentioned something about the Group. Hare abruptly told Bob to finish his drink and said nothing after that, including the trip back to the plant.

The next morning Bob was summoned to Hare's office and motioned over to sit on the couch. This was known as "couch time" by the employees. Hare chewed Bob out for mentioning Group business in public. Social time was not for discussing business according to Hare, especially because you never knew who else would be listening. Hare would not break his own rule to reprimand Bob in public or even outside of the group's facilities. He waited until business hours the next day.

GV discovers video

So, when the Grass Valley Group was still struggling to stay viable TV was to a point where color TV was rapidly ascending and video recording was becoming standard in most broadcast facilities. RCA was at the top of the broadcasting equipment food chain, and Ampex was itself becoming a force in the industry. In the 60s Ampex started branching into cameras and other broadcast equipment. GE, Marconi, Philips, and other large and small companies where selling to broadcasters. Did the industry need another small outfit up in the "boondocks?"

In 1963 during a company brainstorming meeting it was suggested that they should do something for the television market. Hare ran the idea by Harry Jacobs, who had worked for him at the Airborne Instruments Laboratory during the war, and had returned to KGO, the San Francisco ABC owned station. Harry said GVG would have a hard time competing with RCA, Ball Brothers, GE, and others. But he said he would like to visit Grass Valley and he brought a ubiquitous piece of equipment with him, a video distribution amp, or DA as they were called. The DA he brought was a vacuum tube device. They were simple and straightforward devices and sold for about $350 each (in 63 dollars). Harry suggested some refinements. In short order GV designed a video DA. But the Group's was solid state. Under the Grass Valley name the company never made a vacuum tube device.

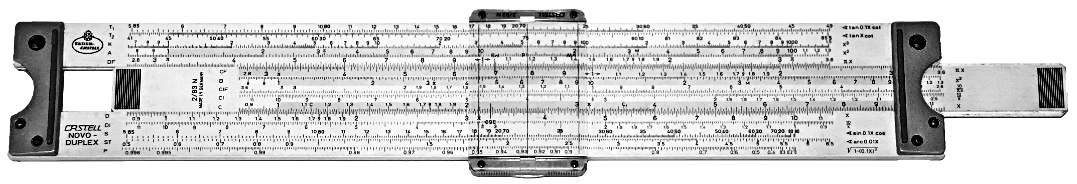

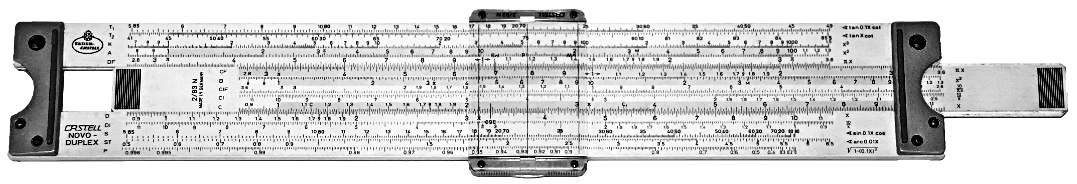

This was at a time when engineers still used slide rules. Forget about today's hardware description languages, or earlier Spice circuit simulation, or more ancient programmable calculators, or any calculators. This was not even the dark ages of modern system design, nor even the iron, or bronze age. This was the tin age. While electronics had progressed, the tools to design, build, and test were rudimentary at best.

In the meantime, sales for their existing audio amps picked up and they got big orders from radio stations in New York and New Orleans. It helped keep the doors open and the lights on. In October 1963, Herby Hartman, chief engineer of KCRA, the NBC affiliate in nearby Sacramento, joined the group. He, Bill Rorden, and Hare put the final touches on the 700 Video DA.

About the same time Hare's son, Stephen graduated with an Electrical Engineering degree from Stanford and went to work for the group. Steve was tall and lanky, and a good athlete, like his dad. Also like his dad he was a free thinker, and there was occasional friction between them. Most of the group called him Corky after Corkhill, his second middle name, which was the same as his dad's.

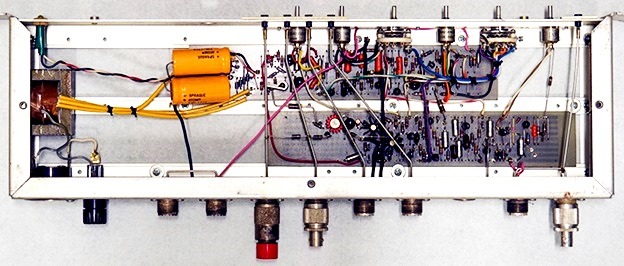

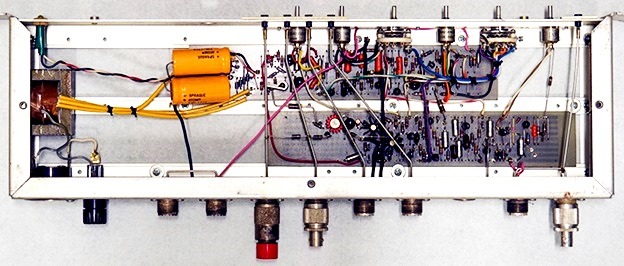

First Grass Valley video distribution amplifier (VDA or just DA). It was offered in two forms. The one on top could be plugged into a frame that held multiple units. Or the stand-alone version that mounted straight into a rack.

In early 1964 Hartman took the new DA to New York City and showed it to CBS, which was not interested, but ABC New York was. Hans Schmidt of ABC spent a week evaluating it. Rorden and Hartman went to the NAB in Chicago that spring. The group, not being a member of the NAB as they could not afford it, set up a demo in their hotel room next store to the convention center at what was then the Hilton hotel. They lured attendees they ran into to come to their room and see the unit. In the next few months, the company received orders for the model 700 and a new modified 705.

This is not a prototype, but a regular production early vintage Grass Valley video product. It used a generic circuit board with long copper traces along it's length. Those traces were hand cut to configure the board for each different product!

ABC

1964 Republican Convention

ABC's normal supplier of DAs and similar equipment was not going to be able to deliver the equipment needed for the upcoming Republican Convention from San Francisco's Cow palace, and Harry Jacobs called and said if the group could deliver 30 DAs and ten proc amps, they would buy them. Hare asked, "What the hell is a proc amp?' Hare had never heard of a processing amp but agreed to build 10 of them. He was told to call Frank Haney in New York and he would give them the specs. This all happened on a Monday. Tuesday afternoon Rorden and Hare went and bought a TV so they could test what they were doing. By Wednesday they had a working breadboard in a vice. They called up Jacobs and said to come see it. He showed up Friday and the group already had it in a case. ABC then gave them the order. All went well with the equipment at the convention. ABC became an important customer. It would be safe to say ABC was GVG's most important customer, at least into the mid 80's.

This ability to take an idea and transform it in short order into a shippable product was one of the Group's main assets early on. We touched on this story in the last chapter, a couple years after the model 700 was out an engineer from RCA called and said they wanted to license the Model 700 DA. Hare said they were obsoleting the model line and that he told the RCA engineer to just go ahead and copy it, he did not care. Hare explained to the RCA guy, that is where the Group had the advantage over RCA. GVG sees a need and simply makes it in very short order. RCA has to get one or more committees to approve an idea, then design the circuit, send it through drafting, assign part numbers to all the components, make requisitions to purchasing, and it is now two years before the idea is shippable. Bill Rorden once said that they discovered there was more ignorance in the video business than in the audio business, and the Group proceeded to take advantage of it.

Even into 1965 the company still had no sales department, nor did it do any advertising. At that year's NAB convention GV joined the NAB and had a low-cost booth that had a modest display. It was enough that orders increased over the next few months. It was at this time that the rise of UHF took off, and so the customer base was increasing. The competition was still tough, with RCA offering just about everything a broadcaster needed.

GVG did not even have a drafting department. New products and anything needed to build, and test products were done with informal documentation, and not blueprints. Rorden and Hare could produce prototypes in days, or at most a few weeks. From their early background with transistors they knew that the mainframe computer industry became the largest user of transistors. The type of transistors that these key players like IBM used, GVG used because the more that are produced ensured that those would be the most reliable.

Now a Video Company

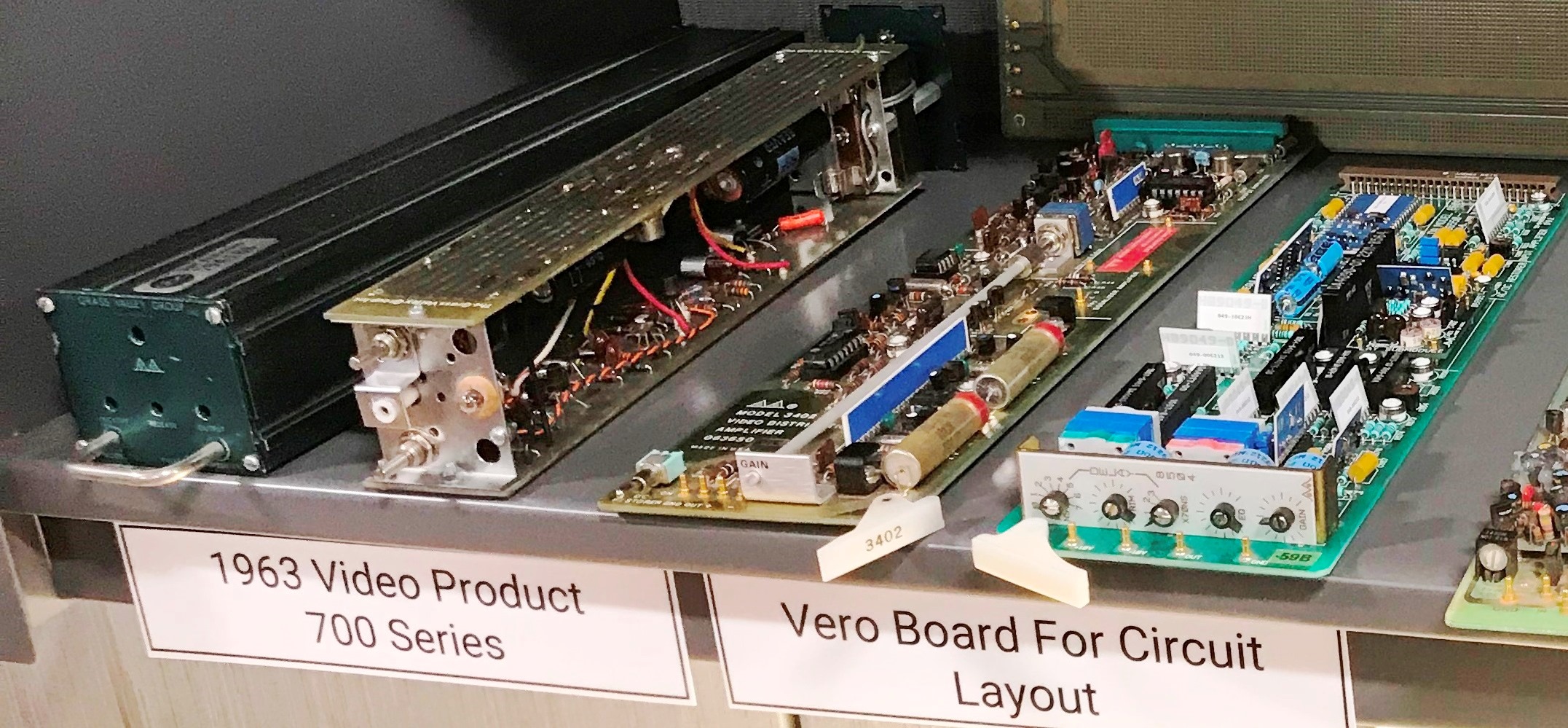

Early Grass Valley video products

Apart from the video DAs and Processing Amps, the majority of the first 70 of GVG products were never produced to take business from another company. In this way they did not have to compete head to head early on, and thus staying clear from the hoofs of their larger competitors. They would innovate and create new markets. Their developed products were based on the needs of engineers working for the networks in San Francisco and Los Angeles. As television was evolving new problems arose and the solution often involved new ideas. GV had an advantage in that Rorden, and Hare could take these new ideas and turn them into products in very short order.

At one-point Hare thought GV was charging too much for a piece of equipment, called a Sync Generator. So GV gave all who had bought one a $500 credit. GV had a philosophy of not charging too much for equipment. They took the cost of producing a piece of gear and added 40%. If that amounted to what the customers were willing to pay, they offered it. If not, they simply did not produce them.

By 1966 orders were coming in faster than they could fulfill them. Bob Johnson, Stephan Hare, Bill Rorden was working every Saturday to keep up. Hazel Hare made almost daily trips to the Sacramento airport in a station wagon filled with boxes of equipment. This would soon be taken over by a dedicated driver and van. That year the ABC Television Network bought 37% of their products sold.

First GVG Building on site

The property that Hare bought back in the last chapter, on Bitney Springs Road, came to be known simply as Bitney Springs. The group now had the money to landscape the Bitney Springs property. Joe Ruess, an area landscaper, and nursery owner was given the task. He naturalized Iris and Daffodils. In the coming years, the entrance to the plant became known as Daffodil Hill every spring by the employees. The company also planted a garden every spring with corn, green onions, carrots, tomatoes, peppers, and summer squash. They also planted peach, apple, apricot, and Black Mission fig trees. The fig being Hare's favorite. There were grape vines that bordered the plot, possibly because of Hare's childhood recollection of his father's vineyards.

Hare hated to see any life-form die, from insects, mice, to the many rattlesnakes that called the property home. He never wanted to personally see any die. Even though he once lost a dog to a snakebite. If there was a rodent or bug problem, it was expected to be taken care of out of his sight.

The Bitney Springs site always faced a fire danger. Dr. Hare once said that if there was ever a fire that came through and took out the trees that he would have to move as he would not be able to stand the desolation. Much of the property had Manzanita on it. If ignited it burns very hot and is difficult to extinguish. They kept a gasoline powered pump with attached water hose at the lake near the main building. GVG's maintenance crew spent part of their daily schedule clearing fire lanes and breaks through the brush to minimize the spread of fire if it should erupt. They even created another pond to increase the amount of water available to fight a fire.

Building 3 - Carefully nested among the trees

Most of California, the Sierra foothills included, have a Mediterranean climate where the winters are wet, and the summers are dry. Most of the rain happens in the winter, and often an entire summer will see no rain. The rain that does occur in the summer is usually due to thunderstorms, with the accompanying lightning and the resulting fire hazard. The state's nickname, "the golden state," came as much from the dead grass covering the hills in the summer, and the golden poppies that rise in the spring, as to the discovery of gold in 1849. That said, there is a closed mine on the Britney Springs property.

By 1966 the Group had grown substantially. Sales doubled over the year before, and net profit increased fivefold, and the company's net worth tripled. Many television facilities would historically build their entire facility with all RCA equipment, as that company made most of the technical equipment that a broadcaster would need, from cameras, all the way through the food chain to transmitters, and even the antennas that were mounted at the top of the tower. By-the-way, those antennas where not like the ones that dotted most roof tops back then, but monsters that could weigh 10 to 15 tons. That was because of the mass of metal that was required to handle the massive RF power emitted by them. The mass was needed not so much for the RF, but the heat that was part of the byproduct of radiating the signal out towards the horizon.

Now more television stations were specifying GVG gear sprinkled in with the RCA, GE, and other large vendors when equipping a station. The volume of product being sold and produced had increased to a point where the Group needed to consider building a second building. Since Hare did not want to take trees out of the current property, he put an option on an adjacent property that was an open field once used for cattle grazing. By the end of the year the Group owned that property and promptly set up to create a building identical to the first, mainly to save time as orders were increasing and lead times were getting longer.

Business grew enough that Hare did not want to accept government sales, especially when the State Department wanted to order more telephone gear. They now had far more lucrative items to produce. It was not that the Group would not take an order for equipment from government agencies, if it was a standard off-the-shelf product, with standard off-the-shelf options, then it would be accepted.

Also, in 1966 the model 700 DA was redesigned and became the model 900. The 900 became a staple in broadcasters equipment racks for the next 20 years. With increased success the Group showed up at NAB in 1967 in a professionally designed, albeit modest, display booth. Orders were strong enough that Hare was worried that the Group might have trouble filling the coming orders in a reasonable amount of time. To anticipate the fulfillment requirements from sales, a production manager was hired for the first time. Also, for the second time in a year the circuit board assembly or "stuffing" department was increased.

The group was now to a point where they could afford to purchase real video monitors from the industry standard at the time, Conrac, instead of buying consumer TV sets and modifying them to work as video monitors, a process known as "jeeping." But the company still had no sales department, even though the company was making a 21% net profit after taxes at that point.

In 1967 Hare decided he wanted to take the company public to increase the capital available for growth, but to also lower the tax rate the company was occurring because of retained earnings. More capital would allow for more retained earnings. It would allow for easier recruiting of engineering talent as the company could now offer stock options. It was also at that point, mainly for appearances, that an affiliated sales company was formed with Si Krinsky as its president, with him getting 20% of the sales company stock. Krinsky was a manufactures rep, who represented a number of similar companies as their salesman. Since he already knew GV and could sell its products, although he was initially reluctant, he was eventually convinced to concentrate on one company, Grass Valley.

1967 was a banner year with sales and net profit up 47% and 66% over 1966. Sales came in at $1.365 million, the first year they broke the million mark. The company went public at $10/share. Besides allowing the company to offer stock options to attract engineering and management talent for future growth, it would also make it easier for the growing company to acquire other companies.

In December of 1966 Hare went to Palo Alto and hired three engineers: Robert Cobler, Jerry Sakai, and Bill Barnhart. Cobler came to work from CBS, where he was in charge of putting together the first color studio. "I was offered a job at The Group mostly because I was the only guy familiar with some of the equipment they wanted to manufacture," Cobler said. The company he said, "were getting pressure from the sales company to make switchers, so that's what we did."

Switchers, or video switchers, or as the British say, "vision mixers" became huge for the company as we will see shortly. The Group would become the dominant player in video production switchers introducing their first a year later, in 1968. Switchers are devices that allow all the layers of graphics, effects, and a myriad of sources to be integrated into a complex mosaic of video. Oh yeah, this is all done in real time while the newscast, sporting event, or entertainment show is happening. Let us introduce this piece of gear that became so important and central to the company.

900 modules: Soon the Group was making numerous video processing products that could be mixed and matched in a single frame

Moving up the food chain: Video Production Switchers

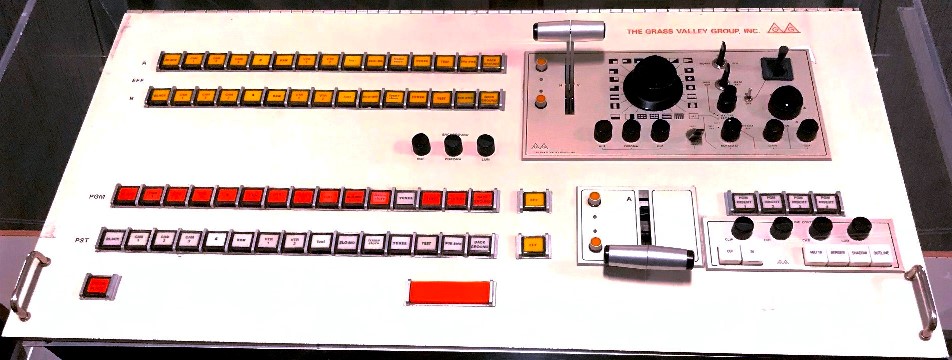

First Grass Valley Group video production switcher. Quite crude by today's standards. But customers loved the tactile feeling of the pushbuttons and the fader bars (T-handles)

Besides the control panel the switcher had a separate electronic chassis.

The top part of the chassis shows a frame similar to the one above in the last section. The Group was gaining the prowess from earlier products to create more complex video products.

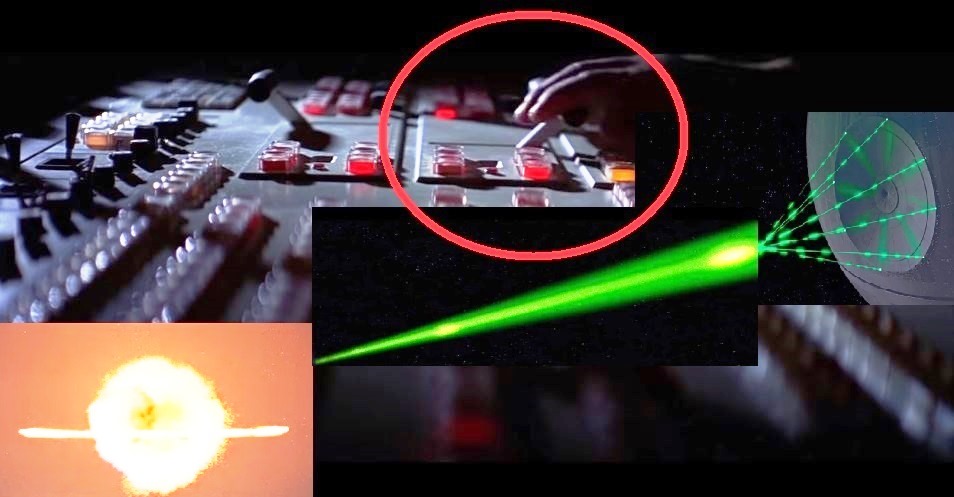

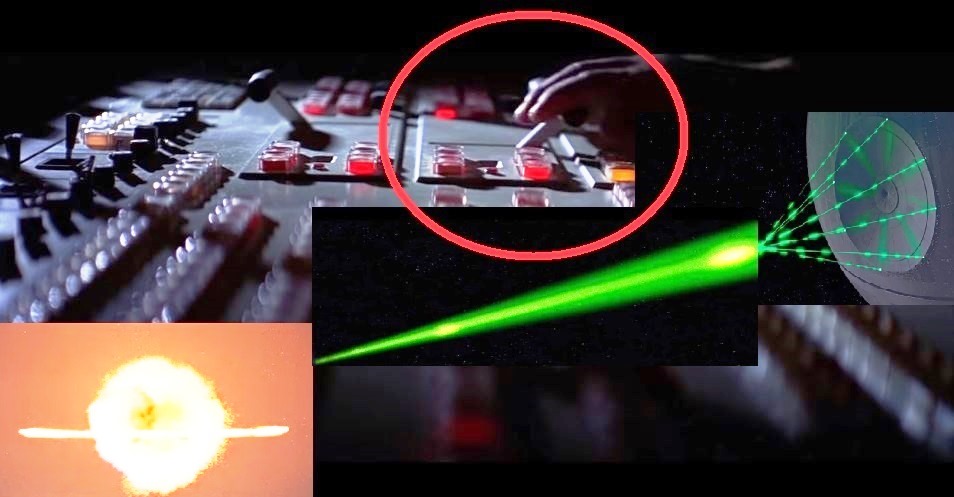

A video production switcher has historically consisted of two components, an electronics chassis, or tub as it is sometimes called, that has most of the electronics, and a control panel, that since the 60s has looked like something that should a be prop in a space mission control scene. In fact by the mid 1970s the group had enough of the high-end video switcher market that one of the props used to destroy Princess Leia's home planet of "Alderaan" in the first Star Wars film, was a video 'fader bar' on the next generation of Grass Valley switchers, the 1600 video production switcher, which was introduced in 1973.

GVG 1600 second generation video production switcher control panel

GVG's first switcher commenced development in the fall of 1967. The company had 30 employees.

Hare was counting on the introduction of switchers as a way to expand the company. The plan was to get the switcher to the 1968 NAB the next spring in Washington, D.C. To accomplish this goal in such a short period of time, the four new engineers just hired together with Engineering Vice President Bill Rorden, spearheaded the project.

Since production switchers were not new to the industry, the 1400 project team's first task was to assess the competition. Hare commanded that their second task was to figure out how to do it better. Product reliability and useability became areas of primary concern. According to Jerry Sakai, "At that time it was not uncommon for a customer to spend weeks getting a new production switcher online." Sakai said that one of their design goals was that the 1400 would work when it came out of the shipping crate. To accomplish that he said that they had to do "some clever things-not fancy, but clever."

Beginning with an overall system layout, every control and every circuit contained in existing switchers was thoroughly analyzed and then re-engineered to provide a reliable. user-oriented switcher. Cosmetics were secondary in importance to the switcher's dependability. This is a very true statement if you compare the 1400 to the other switchers that soon followed from the group.

While certainly not the most critical, one of the more perplexing problems the designers faced was how to mount the pattern "positioner." This is one of the first instances of what today would be called a joystick. They needed a hemisphere-shaped mount that would allow free movement of the joystick. A fancy way of saying a sphere cut in half. Originally they found a vendor of such a part. But before the switcher was complete they found that the vendor couldn't reliably deliver it. The solution? They cut a pink baby rattle in half, drilled a hole in the center, and painted it black. So the joystick is mounted on the top of the rattle. "We must have bought every baby rattle in Grass Valley," reflected Cobler.

NAB arrived after five months of six-day weeks and 12-hour days. The final week before the show was a marathon session. "I spent the last 36 hours sitting at my bench debugging a design and then building two breadboards of it," Sakai recalls. "When the truck finally left, all I could do was go home and sleep."

This the group would find in later years, as many vendors of high end complex systems headed for NAB, would be the norm. Product marketing and management often couldn't decide upon what they want to show at NAB until late the year before, and even sometimes, heaven forbid, not until into the new year.

The 1400 production switcher displayed at the 1968 NAB show was fully functional. With many vendors, and even a couple times at GVG, it took some "smoke and mirrors" to make a semi-functional piece of equipment appear to be fully operational. The 1400 displayed that year contained 12 video inputs and a video mix/special effects system. It also offered 24 wipe transition patterns, effects re-entry, and external, matte, and chroma keying.

The 1400 displayed was bought right off the floor of the show by KVII of Amarillo, Texas. GVG was unprepared for the excitement the new switcher had generated and had not priced the unit yet. Hasty meetings were held to establish a $30,000 selling price. Very inexpensive by today's switcher standards.

The person who sits at the switcher control panel is usually called the "technical director," or TD for short. The reason for the title, was at the dawn of television, equipment was unstable, and the FCC had many rules as to what could be aired, not only content wise, but technically also. This was because the electronics in the TV receivers of the day did not have a lot of processing power and it did not take much wrong with the signal before sets would not work well, and viewers would complain to the FCC. So the TD was the final arbiter as to what went to air, and it was the switcher that selected what combination of video made up the final program montage. Today that is no longer so but the title lives on.

This is not to say that the person who sits there today is not skilled, they are and must be, but not with the technical expertise that TDs once had. Today switchers have grown so capable, and complicated that not all people are able to occupy that position, and not all are equal in skill set. It has been compared to flying a plane, or even playing the piano. Using the flying a plane correlation, most pilots can keep the wings level and do simple maneuvers. Only a few are any good at doing acrobatics. The same with the switchers. Many claim most users only use 25 percent of its capability. The virtuosos are in high demand.

TD at the switcher control panel (circled) in a modern production truck. The director and producer are to the left.

The layout of the control panel has always been rows of buttons, where each row seems to have the same labeled pushbuttons. But there is a method to all the madness as they are color coded in groups of two to four rows. The top group might be white, the next group of two to four might be yellow, then orange, etc. The bottom group is usually red. Each group allows for a set of layers and mosaics to be created. The elements put together in one set of rows can then all be layered on top another group and so on. So, the result can be quite complex. The whole control panel represents a trickle down effects factory where a TD might setup a split image in the top group, and then add a background in the second group, and then lay a banner graphic over everything in the third row.

The bottom line is that all the buttons allow the TD to make changes very quickly as a program or event unfolds and it allows them to see at a glance how the "freight train" so-to-speak is coming together. The TD does this under the direction of the shows director who calls out the effects and camera cuts and dissolves. The director is under the supervision of the producer who owns the vision and content of a show and helps guide the director to make that happen. The final result is that the integration of all the sources into layers of video, graphics, and other effects. All in real time.

By mid-68 GVG had received requests for quotes on the 1400 amounting to over a million dollars and had firm orders for five switchers. Switchers were not cheap devices that, depending on the options, could easily break $100,000 in 1960s money. Over the years switchers had shipped with price tags of over $500,000.

Grass Valley did not invent the switcher, they had formidable competition waiting. Of course there was RCA, along with other established vendors with names like CDL, and Vital. What made GV think they could compete, besides the fact that they had competed in other, albeit simpler areas? First, a lot of people in the industry wanted features that were not widely available yet, and GV had the audacity to think they could provide a more capable product where the desired features came standard. Also with the DAs and processing amplifier products that they already had, they realized that they had much of the internal electronic infrastructure required already covered.

But where they really made their mark was they thought they could make a superior control panel with a more ergonomically human interface. Which they did. The tactile feel of the individual buttons on the control panel had a more positive and smoother feel. Grass Valley patented a couple aspects of those new switchers, and soon TDs started referring to the Grass Valley look and feel of their control panels.

Cobler said the key was superb engineering. "Reliability was the factor," recalled Cobler, who stayed with the company 25 years. "Our switchers worked right out of the box. It was a plug-in, and you didn't even need a screwdriver." Switchers up until then were notorious for needing lots of setup before they were usable. Vital and RCA were notorious for switcher reliability. Switchers were vital, no pun intended, to the operation. While losing a camera would hurt the show, losing the switcher would shut down the show. It was not uncommon for users of RCA's commonly used TS-40 switcher to refer to the prefix as "Tough Shit!"

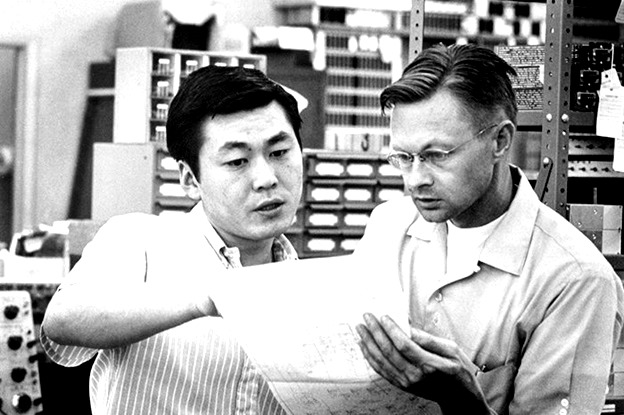

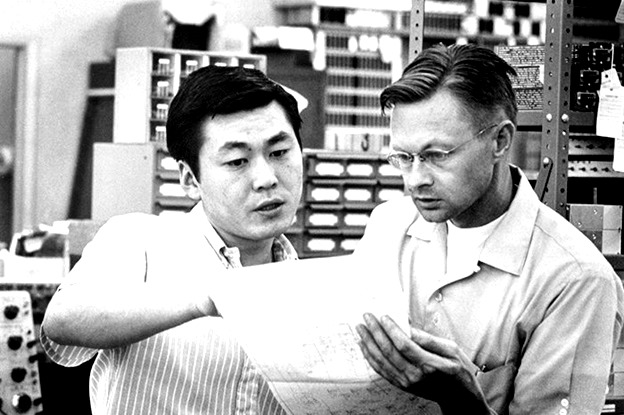

Jerry Sakai and Bill Rorden

Hare put Cobler in charge of engineering and design of the switcher product line. Jerry Sakai became the production manager and was tasked with fixing a production bottleneck with circuit boards that didn't pass test early on. Growth was such that three more buildings were added in 1969. The buildings on 120 acres placed amongst the trees looked more like a college campus than an industrial park. By 1970 half of sales were for video switchers. For a long while after that, even today, GVG dominated the switcher market.

Building 4

GV simply kept adding refinements and features faster than anyone else could. New special effects were added, and a new integrated circuit was used in the video switchers mixing circuitry that eliminated the need for studio technicians to make periodic and tedious adjustments.

Growth did come with a setback in 1969. The small company, the "we're in this together" culture faded somewhat when the production and maintenance workers were organized by IBEW, and when they were unable to reach a wage agreement the workers went on strike in August. Replacement workers were hired, and production continued. After months of no agreement the union filed a claim with the NLRB that the company was not bargaining in good faith. The NLRB ruled against the union, and it eventually abandoned its efforts to obtain a collective bargaining agreement with the group. Hare never quite thought the same of the rank and file from then on.

Financially On the map

On January 19th, 1970, the company's stock was listed on the American Stock exchange with the symbol GVG, as up until then it was an over the counter stock. The rest of the year was not that positive for the company as besides a sluggish economy and concerns in the television industry about what the approaching January 1st, 1971, ban on cigarette smoking might do to ad revenue, the industry was cautious in investing in capital equipment. While the group still made a profit, it was not what the previous years were.

"ABC liked everything about our switchers," quoting Jerry Sakai, "but they were a little nervous about this little company we had out in the boondocks." But none-the-less ABC continued to be a major customer of the Group, and in ways looked to the company as their engineering lab. While NBC obviously had RCA, and CBS had there renowned CBS Labs, ABC had a small research and engineering group that paled in comparison to the other two. And as we have seen earlier ABC was as innovative as anyone.

In 1970 Roone Arledge struck again with something thought foolish at first. Although CBS had done a few Monday night NFL games, as had NBC, with a few Monday Night AFL games, neither network was interested in regular MNF. Rozelle approached ABC, which was also reluctant, but he threatened to sign with Hughes Sports Network. ABC, fearing that its weak Monday night lineup would prompt many ABC affiliates to carry the game, agreed to air them. The stroke of genius as we discussed earlier, was that Arledge turned it into a spectacle with drama, story, and a new strange announcing format, which became a must see event.

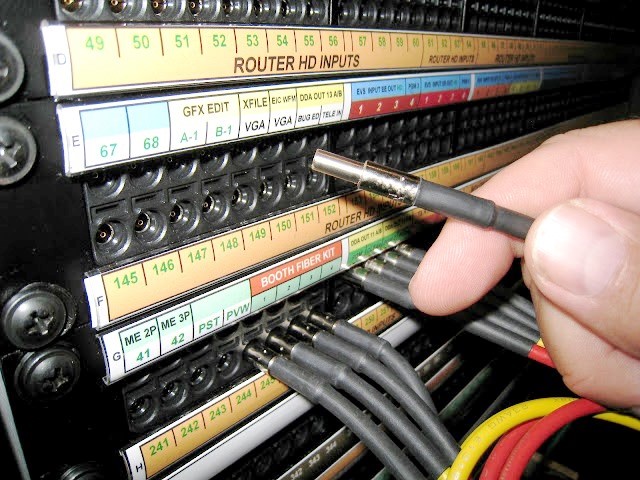

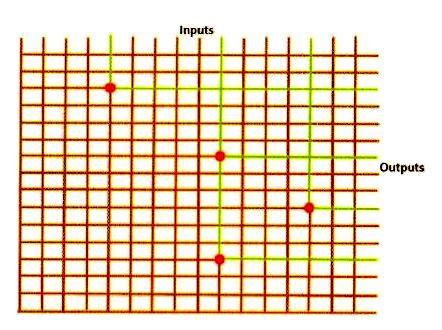

Later in the 70s, but indicative of ABC's and Grass Valley's mutual symbiosis, Julius Barnathan, VP of Engineering of ABC, another visionary as we mentioned earlier, had an idea for a new product and talked extensively with Rorden and then traveled out to meet with him and Hare. His idea was what is known as a video/audio routing switcher. He wanted something that would allow as many as 60 output video and audio feeds to select any of 100 video and audio inputs. Up until that time if you wanted to do that it was done with manual patching like you see in an old phone operator station. To do that required 6,000 electronic switches, or crosspoints as they are called, for video and another 6,000 for audio. It occupied eight full sized equipment racks. It cost $525,000. It was the first of its kind. It did not come from CBS Labs, or RCA, it came by taking an idea from ABC and making it a reality in Grass Valley.

As the 70s started GV made its first presence at the International Television Symposium in Montreux, Switzerland. That is NAB for the world. In 1971 Sales offices were opened in six major cities, and in 1972 they reached $4,658,000 in sales. The milestone then was that no one customer contributed more than 5% to sales, and this was the first year the group paid a dividend to stockholders. In 1973 GV introduced its second generation of switchers, the 1600 at NAB. The electronic architecture was totally new, and the switcher was an order of magnitude more capable than the 1400. This new offering also refined the control panel interface that had won over so many TDs. As we will see later, it was the control panel, and human nature that made GV switchers so entrenched. In 1972 sales were $4.7 million, with earnings of $1.066 million, and total employment was 130. Outside suitors took note.

1973 marked the first ownership change of many to come for the company. This first marriage was to Tektronix. Under the merger plan ironed out, approximately one share of Tektronix stock was issued for every three shares of Grass Valley Group. This involved approximately 500,000 Tektronix shares. Culture, direction, and inertia were about to change.

As the company grew, so did its Bitney Springs campus. Photo at the site's height.